Puella Magi Madoka Magica the Movie: Rebellion Official Guidebook "Only You"

Puella Magi Madoka Magica Movie The Rebellion Story Official Guidebook "Only You", a compilation on a wide variety of information about The Rebellion Story, was released on April 12th, 2014.

Contents

- Illustration gallery, containing illustrations from magazines and other sources

- Summary of the movie

- Gekidan Inu Curry Artwork Gallery

- Staff Interviews

- Chiwa Saito and Kaori Mizuhashi

- Aoi Yuuki and Emiri Katou

- Eri Kitamura and Ai Nonaka

- Chiwa Saito and Kana Asumi

- Akiyuki Shinbo, Aoki Ume, Gen Urobuchi, Mitsutoshi Kubota and Atsuhiro Iwakami

- Yukihiro Miyamoto

- Shinsaku Sasaki

- Junichiro Taniguchi and Hiroki Yamamura

- Yota Tsuruoka

- Yasuhiro Okada

- Yuki Kajiura

- Gekidan Inu Curry

- Takashi Kawabata

- Koichi Kikuta

- Takashi Hashimoto

- Motoki Sakai

- Yoichi Nango

- Shinichiro Eto

- Hitoshi Hibino

- Izumi Takizawa

- Rie Matsubara

- ClariS

- Kalafina

- Yuuko Gotou

- Tetsuya Iwanaga

- Junko Iwao

- Ryouko Shintani

- Seiko Yoshida

- After-recording comic by Hanokage (also featured in Manga Time Kirara Magica Vol.10)

Settings

ART SETTINGS

Park with a Hill

A park where Madoka and Homura converse one month after Homura’s transfer to Mitakihara Middle School. The flowerbeds are designed with mosaic art made from flowers, grass, and dragon’s beard plants.

Mami’s Magic Room

The room where Madoka and the others corner and purify the Nightmare in their first battle. Its warm atmosphere is created by the high ceiling and wooden walls, resembling a log house.

Mami’s Dressing Room

The room where Mami is seen when Hitomi’s Nightmare appears. It is quite spacious and decorated with cute items like stuffed animals and penguin-shaped matryoshka dolls.

Waterside Café

The café where Homura calls Kyoko. Inside the dome-shaped building, trees and grass are planted, creating a lush environment.

Ghost Town

The ghost town where Homura and Mami engaged in intense combat. It is divided into three areas: the Uppermost Area (upper), Battleship Island Area (middle), and Cemetery Area (lower). According to the notes on the setting artwork, the interiors of the buildings in the lowermost section are all graves.

Bus Stop on the Bridge

The bus stop Homura headed toward while talking to Kyoko, who was at the arcade. The differing heights of the round streetlights and the multiple bus timetables lined up are striking features.

Bus

The bus Homura and Kyoko intended to take to Kazamino City. Homura also used it to check her physical condition. It is a double-decker bus, with wooden benches on the second floor that are gently curved.

ULTIMATE MADOKA - CHARACTER DESIGN NOTES

The color settings mention details such as "The ends of the hair should always remain outside the frame" and "The wings should not stick to the back," showing various instructions for the animation process. The elegant expressions, white-based dress, and the cosmic expanse inside the skirt create a very divine impression.

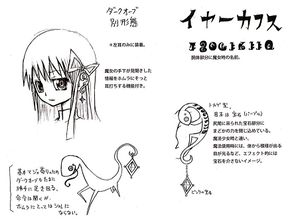

DEVIL HOMURA - CHARACTER DESIGN NOTES

Homura, as a devil, is characterized by her ribbon, a dress with an open back, and black wings. The underside of her skirt spreads into a dark abyss. Her sinister smile in the expression sheets perfectly captures the look of a devil who has desecrated a god.

Staff Interviews

Opening theme

"Colorful"

■ Song by: ClariS

■ Lyrics & Composition: Sho Watanabe

■ Arrangement: Atsushi Yuasa

The non-credit version of the opening animation, included as a bonus feature on the Blu-ray and DVD, is introduced here. This animation includes numerous scenes that hint at the storyline of the main film: scenes with Homura alone, shadows and ear cuffs associated with Homura’s transformation into a demon, and many other suggestive elements. Additionally, the tower with the interference-blocking field set up by the incubators is depicted.

Opening Animation

Storyboarding & Direction: Takashi Kawabata

How did you come to be in charge of storyboarding and directing the opening?

Initially, I was only asked to handle the main film. However, partway through, I was also requested to work on the opening animation. Since it was such a valuable opportunity, I happily accepted.

What was your impression when you first heard "Colorful," and what did you discuss with General Director Akiyuki Shinbo?

I felt it was a fast-paced song, similar to "Connect" from the TV series. Director Shinbo said, "I’d like to show a cheerful side of Madoka and the others, something we don’t often see in the main story."

Were there any particular points you focused on while storyboarding and directing?

Since Madoka☆Magica isn’t a straightforwardly happy story, I aimed to create visuals that feel cheerful at first glance but leave a heavy emotional impact upon repeated viewing. I wanted to convey the disconnect in Madoka and Homura’s feelings for each other, Homura’s sense of loneliness, and the transition from the TV series’ ending to the movie. If that came through in the animation, I’d be very pleased.

Ending theme

"Kimi no Gin no Niwa"

■ Song by: Kalafina

■ Lyrics/Composition/Arrangement: Yuki Kajiura

Silhouettes resembling Madoka and Homura sway to the rhythm of the song, and at the end, they hold hands and disappear into the distance.

Ending Animation

Hirofumi Suzuki

Could you share your impressions when you first heard "Kimi no Gin no Niwa," or anything you discussed with director Akiyuki Shinbo?

When I first heard "Kimi no Gin no Niwa," I thought it was a rather eerie piece of poetry. As with the TV series, there were no specific instructions from the chief director, so I was given complete freedom to create it. However, this freedom led to the content undergoing multiple revisions up until the very end of the process. Initially, I considered directly depicting the lyrics in the animation, but that turned out to be a bit too dark, so I made some changes. I aimed to keep the atmosphere of the visuals not too far removed from the TV series.

Were there any particular points you were particular about while creating the ending animation?

The cut where the two characters hold hands and run off together was something I had decided on from the very beginning. Regardless of the film's conclusion, I wanted to include that scene. Initially, the two characters were meant to be "girls who resembled Homura and Madoka," but they ended up becoming exactly "Homura and Madoka."

Is there anything else you considered or focused on?

The full-length chorus in the ending posed a challenge because its repetition of the refrain two or three times made it difficult to arrange the visuals. I had an impression that theater endings often use plain backgrounds with only credits, so I struggled with balancing the visuals and the song.

What are your overall impressions of being involved with this work?

After the TV series and the earlier movies, Puella Magi Madoka Magica has evolved into an unique movie unlike any other. It seems to be hugely popular, and I feel incredibly fortunate to have been able to participate in such a remarkable project.

Akiyuki Shinbo, Ume Aoki, Gen Urobuchi, Mitsutoshi Kubota and Atsuhiro Iwakami

THOUGHTS AFTER SOME TIME HAS PASSED SINCE THE RELEASE

It’s been about six months since the release. How are you feeling now?

Shinbo: My memories of the project have faded quite a bit (laughs). Right after it ended, there were a lot of emotions, but now I feel pretty calm.

Urobuchi: It's like a sparkling memory for me. It’s like, "Wow, I was really shining back then" (laughs).

Aoki: I also feel like it was such a long time ago, especially since I was involved quite a while back. It feels like it was a distant past. However, some people I know who love Madoka Magica would report to me every time they went to the theater, posting on Twitter, saying things like, “It was a great six months." Thanks to all those supportive people, I somehow still have a sense that this project was ongoing until recently (laughs).

Kubota: For me, since I just finished the retake work for the home release packaging a few weeks ago, it still feels pretty fresh (laughs).

I see (laughs). How about you, Iwakami-san?

Iwakami: Well, quite a bit of time has passed, so it feels like a memory now. However, Kubota-san and I have been invited to the Japan Academy Awards ceremony soon. Receiving that kind of recognition and still hearing people say, "It’s amazing," makes me really happy.

THE NEW PROJECT THAT STARTED BEFORE THE TV SERIES ENDED

As for the production of the new chapter, could you tell us again how this project started?

Iwakami: It was around mid-March 2011 when Urobuchi-san first gave us a plot outline, something like "Madoka 2".

Urobuchi: I think it was still during the time the TV series hadn't finished airing yet.

Kubota: Yes, it was right around the time of the earthquake.

Iwakami: That’s right. It was a difficult time, but we were already thinking, “Let’s do something next with Madoka Magica”. At that point, we hadn’t yet decided whether it would be for TV or a theatrical release. First, we were focusing on how to finalize the idea, and then we planned to think about the format afterward. So, the first step was to get the ideas turned into a script.

Kubota: I remember that when the initial plot was submitted, Iwakami-san said something like, “Wouldn’t this work better as a theatrical release?”

Urobuchi-san, do you remember what you were thinking when you wrote the initial plot?

Urobuchi: It was a hectic time, so my memory is a bit hazy, but I do remember that the beginning was tough. I didn’t know how to connect it to a sequel. I had come up with an epilogue of sorts, but I thought, "This feels like Jacob’s Ladder" (a 1990 psychological thriller film about a Vietnam War veteran experiencing a nightmarish reality). I remember questioning myself—"Is it okay to end it with such a deceptive conclusion?" But at the same time, I also felt like, "What else can I do?" So, I submitted it like that, I think.

Does that mean that the plot you first submitted was similar to the final version of the new chapter that was actually produced?

Urobuchi: In the beginning, yes. The idea that the world in the new chapter is a barrier created by Homura—that was the central concept of that plot. However, at that time, the ending I had in mind was that the barrier would dissolve, and Homura would pass away peacefully.

At that stage, how was the idea communicated to Aoki-san?

Aoki: During the TV broadcast, I had heard that there might be something new, but it wasn’t definite, so my reaction was, “Huh? Are we really doing this?” I was really happy, but also surprised.

Iwakami: The plot kind of just arrived out of the blue, didn’t it? (laughs).

Aoki: Yes, exactly. I didn’t know what the chances were of the sequel actually happening, so when something fully fleshed out suddenly appeared in front of me, I was really shocked.

Iwakami: But even when you couldn’t attend meetings, Aoki-san, you always sent in your opinions through memos, right? I always thought your feedback was spot on.

Aoki: ...I don’t remember (laughs). I think I attended the first two or three meetings. I remember discussing in the conference room whether it would be a TV series or a TV special.

Iwakami: Yes, I remember everyone was there when we were having that conversation.

Aoki: The only idea I contributed was just a little bit at the end, something like, “I’d like it to end this way”.

What kind of request did you make?

Aoki: It’s a very minor detail, but in the scene where Homura says to Madoka, “I’ve been waiting,” and suddenly grabs her, the original plot made Madoka’s response sound more unpleasant than in the final version. Her line had a stronger “Stop!” vibe. I remember asking to soften it a bit. I didn’t want it to seem like Homura was doing something that Madoka would dislike. Homura is driven by her love for Madoka, so I didn’t want that to be misrepresented.

I see. Urobuchi-san, when did you start writing the script?

Urobuchi: I think it was right after I submitted the plot. By around summer 2013, the final draft was probably finished.

Kubota: Yeah, it was done by August or September. It didn’t take more than six months to write. The fourth draft was practically the final version, although there might have been some minor adjustments afterward, but nothing major was changed.

Urobuchi: The script lengthened quite a bit between the first and final drafts.

Kubota: That was due to Shinbo-san’s request, right?

Urobuchi: Yes. When working on the TV series, I had a habit of cramming too much into a short space, so for the movie, we took the opposite approach, trying to add more content.

Iwakami: Urobuchi-san’s scripts are always very concise. They’re sharp and to the point.

Urobuchi: That being said, this was my first time writing a movie script, so that had a big impact. I wasn’t sure how to estimate the length.

Kubota: The initial script gave the impression it would run about 70 minutes.

Urobuchi: We significantly extended the magical girl battles at the start. Basically, we decided to expand the happy dream world even more (laughs).

So, you decided to add more content to meet the fans' expectations?

Urobuchi: Well, since we had the opportunity, we thought we might as well take advantage of it.

Did the director have any requests when it came to extending the runtime?

Shinbo: It wasn’t about making it longer, but I did ask for an action scene at the start.

Iwakami: If we go back in time a bit, the structure that includes those happy moments came from Shinbo-san’s desire to show the characters in action again. The plot started with the question of how to create a setting where those characters, including Sayaka, could shine again.

Urobuchi: That’s right.

So, bringing the five girls together was a must?

Kubota: Yes, the idea was that we wanted to see them as magical girls again and, at the same time, in a happy space. That was definitely the underlying premise.

Not just having them appear, but having them all transformed into magical girls, and looking happy?

Kubota: Exactly. I don’t think we had fully decided to make it a direct continuation of the two recap movies from the TV series. The project started from the conversation about how we wanted to bring the five girls together again and see them happy.

So, the idea of reuniting the five girls came first, and it just happened to become a continuation of the story. Did you originally plan to promote it as a sequel?

Shinbo: We debated whether or not to explicitly call it a sequel.

Urobuchi: At first, we were talking about how it could be interpreted as a parallel development, and that would be fine.

Shinbo: I thought it would be more enjoyable if people watched it without knowing for sure.

Kubota: We discussed how it could be seen as just one of the loops Homura experienced.

Shinbo: In the end, we decided to market it as a sequel from the start, but if we hadn’t, I think the audience would have been even more confused. I realized how tricky it can be to promote a movie. It was Iwakami-san’s decision to clearly label it as a sequel, right?

Iwakami: Yeah, that was probably my call.

Shinbo: I think that was the right decision. It prevented unnecessary confusion.

Iwakami: I’m glad you think so.

Shinbo: If people went in unsure whether it was a sequel or not, they might have spent the whole movie wondering, "What is this?" and then it would end before they figured it out. It’s a delicate matter deciding how much to reveal in promotions, but we couldn’t afford to mislead people. I realized that magazine promotions differ between TV and film.

Iwakami: That’s true. TV shows are free to watch, so the approach is different.

Shinbo: We needed to first make sure people were willing to pay to see it. I realized that commercials for movies are different from TV shows too. I mean, there are plenty of movies where the best parts are all in the commercials, and you leave thinking, "That’s all there was?" But if you don’t show enough, people won’t come to the theater.

Kubota: At what point did the idea of making recap movies between the TV series and the sequel come up?

Iwakami: I think it was pretty early on. After receiving Urobuchi-san’s plot, we thought, "This would be great as a movie," and since it would be more enjoyable for the audience to know the TV story beforehand, we decided to release recap movies and then follow up with the new film. I remember that Urobuchi-san’s plot really shaped the format.

Urobuchi: To be honest, if you hadn’t watched the TV series, the movie wouldn’t make any sense (laughs).

Iwakami: I’m amazed that such a high-barrier movie still became a hit (laughs).

While making the sequel, were there any aspects of character development or the story that were influenced by fan reactions?

Urobuchi: Yes, I think so. In the main series, the characters didn’t get much closure, so I think the audience felt a need to "do something" for them themselves. Honestly, I didn’t expect the characters to expand as much as they did, so it was both easier and harder in different ways. Since the characters were already so well-understood by the fans, I didn’t feel the need to dig deeper or make drastic changes, which was a relief. It’s rare for a one-season series to have its characters so firmly grasped and developed. On the other hand, there was pressure because the characters were already fully formed in everyone’s minds, and I couldn’t break that image. For example, it would’ve felt wrong if Sayaka had moved on to a completely new love interest. That wouldn’t have worked (laughs). I knew it wasn’t a series where we could make such bold changes.

Shinbo: But that kind of story for Sayaka is interesting (laughs).

Urobuchi: A new love, only to turn into a witch again? (laughs).

Shinbo: Right, she’d end up repeating the same thing over and over.

Urobuchi: She’d fall in love every time a handsome guy appeared, and then turn into a witch…

Iwakami: Like "Tora-san," constantly meeting new people and getting heartbroken (laughs).

There are many scenes featuring popular pairings among fans, like Sayaka and Kyoko, and Madoka and Homura, showing them in action. Were those pairings something you were consciously aware of?

Urobuchi: Well, those relationships inevitably follow from the original storyline. It wouldn’t make sense for Sayaka to come back and not greet Kyoko at all, for example.

Iwakami: The depiction of Sayaka and Kyoko also expanded a lot during the storyboard stage. It’s not just the dialogue; adding gestures for the characters really adds depth.

Aoki: There was a project for the magazine smart where I wrote letters to Kyoko and Sayaka, and I wrote all sorts of things pretty irresponsibly (laughs). But it made me want to ask Urobuchi-san something. In the TV series, when Kyoko risked her life for Sayaka, Sayaka had already turned into a witch, so she probably didn’t know, right? But in the new film, Sayaka went to the Law of Cycles and then came back. Now she’s close with Kyoko and even says, "I regretted leaving you behind". Does that mean Sayaka knows everything?

Urobuchi: Once you go to the Law of Cycles, you become omniscient and omnipotent, so yes, you can assume she knows everything. In the TV series, Sayaka and Kyoko's story ended almost like a double suicide. But in the reset world with the wraiths, Sayaka ascended alone, leaving Kyoko behind. So in the new story, Kyoko doesn’t know Sayaka in her witch form, but Sayaka knows Kyoko and her actions. There’s even the line about "the boy you loved," so I think her ending in this world is similar to how it was in the TV series. Maybe she did something like a self-sacrificial attack again.

Aoki: I was so happy to see that in the new story, Sayaka seems to understand Kyoko’s efforts, which felt very one-sided in the TV series. It was like, "Sayaka, Kyoko worked really hard for you!" (laughs)

Urobuchi: Thinking about it, Madoka didn’t notice Homura at all until she became a god either. Until then, she was just that scary girl who popped up outside her window (laughs).

With all the character development building up like that, it must have been difficult to introduce Nagisa = Bebe. What kind of discussions did you have about that?

Urobuchi: The idea was that, to properly balance the story, we needed another character besides Sayaka who had become a witch and returned to this world. And if we were going to choose one, the most distinctive witch character would be the Dessert Witch [Charlotte], which led to the creation of Bebe.

So it was Urobuchi-san’s idea. What were everyone’s initial thoughts when they first heard it?

Shinbo: When I first read the plot, I thought, “This could be interesting”.

Iwakami: It wasn’t like we asked from the start to introduce a new character. Bebe really just appeared out of nowhere in Urobuchi-san’s plot.

Urobuchi: I felt that we needed her in that role. And if we were going to bring her in, I thought we should make it as compelling as possible.

Shinbo: I thought, "Ah, I see", and it made sense.

Even though the character was born from the setting, I imagine it was difficult for Aoki-san to bring the character to life through your illustrations, wasn’t it?

Aoki: Yes, I struggled with how much of her witch form’s elements to carry over and how much to leave behind or change. It wouldn’t have worked if she looked exactly the same, but making her entirely different wouldn’t feel right either.

Kubota: You were really struggling with that during the draft phase, weren’t you?

Aoki: I agonized over it quite a bit. I think Nagisa’s design is the one that changed the most from the initial draft to the final version out of all the characters I’ve worked on.

Shinbo: Wasn’t it you, Kubota-san, who came up with the idea to make Nagisa’s hair white?

In Aoki-sensei’s original draft, she had blonde hair, right?

Kubota: Yes, but we thought it might overlap too much with other characters, so we suggested going with a white color. Also, in the original draft, she was a bit older. She was still younger than the other girls, but she was about middle school age. So, her proportions were taller compared to the final design. I think it was Shinbo-san who requested that we lower her age, wasn’t it?

Shinbo: No, I don’t think that was me. I think it was Urobuchi-san who said, “A younger design would be better”.

Aoki: I also remember Urobuchi-san making a request along those lines.

Urobuchi: That might be true. But honestly, I saw many of the designs for the first time when I watched the completed animation. I did know about Nagisa, but Devil Homura was new to me when I saw it in the final version.

Aoki: Sorry about that! We were finalizing Devil Homura’s design right up to the last minute.

Did the staff refer to Homura in her devil form as “DebiHomu-sama” (Devil Homura) among yourselves?

Urobuchi: No, that’s a term we just came up with now (laughs).

Aoki: On set, we called her “Akuma Homura” (Devil Homura) (laughs).

In a way, Devil Homura is almost like a new character. How did you solidify her design?

Aoki: We didn’t really have meetings or anything like that.

Urobuchi: Her character portrayal evolved quite a bit during the storyboard process. In fact, even during the storyboards, there were different interpretations of how to portray her. Up until the last minute, we were deciding how to settle on her final character, and even after recording the dialogue, we had to ask Saito-san to re-record some lines because it was so challenging.

In what ways did her portrayal evolve?

Urobuchi: In the storyboards, she became much cuter. In the script, she was a much scarier character, almost as if she had completely abandoned her humanity (laughs). But during the storyboard phase, she regained some of her humanity, as if she was still partly the old Homura, trying her best to act like a devil.

Shinbo: When you get a script like that, storyboard artists often feel compelled to draw a sly smile for the character, like an evil smirk. I thought we needed to tone down the nuance from the storyboards during the actual animation. However, the first voice recording session was based on the storyboards, so it ended up being quite intense.

Urobuchi: Chiwa Saito’s performance was incredibly scary and dangerous.

Shinbo: Her performance made me think, “This is like Darth Vader”. At the time, I thought, “Yeah, that’s one way to approach it”, but after the recording, I felt something wasn’t quite right.

Urobuchi: Both Shinbo-san and I struggled with deciding whether to portray her as a fully realized devil or a devil in the process of becoming one.

Shinbo: A completely evil, devilish Homura didn’t feel right, but neither did one who was still unsure. In the end, we aimed to capture the moment just before she’s fully consumed by her devil side, a subtle in-between state.

How did you all come to the decision to re-record that scene?

Iwakami: Everyone was feeling uncertain about it right after the initial recording ended.

Kubota: It felt like we had made a bit of a mistake with it.

Shinbo: That night, I couldn’t really sleep well. After the session, Tsuruoka-san (the sound director) asked me repeatedly, “Are you sure you have no regrets?” I started thinking maybe we hadn’t gotten it quite right.

Kubota: The conversation really started moving about two or three days after the recording ended.

Shinbo: We finished recording on a Saturday, took Sunday off, and I think we discussed it on Monday.

Kubota: Yes, that’s right. We confirmed Shinbo-san’s thoughts and then consulted with Urobuchi-san, Aoki-san, and the other key staff members. Saito-san’s initial performance was so well done that it was hard to consider changing it. She had delivered an impeccable performance based on the storyboard, to the point that it felt like it couldn’t be improved.

Urobuchi: I really wish I could’ve been there for that recording session.

Shinbo: If you had been there, Urobuchi-san, you probably would’ve said it was fine (laughs).

Urobuchi: When I listened to the first take they sent me, I thought, “This is perfect!” (laughs).

Iwakami: If Urobuchi-san had been there, we might not have done a retake at all (laughs).

Urobuchi: That’s very possible (laughs). I might have insisted, “This is the only way”. But if we had stuck with that version, Homura would have ended up being portrayed like a full-on monster.

Shinbo: And I think the fans who came to see the movie would’ve been completely turned off (laughs). That was the key issue. As a character, the original version was cool, and I personally like that kind of portrayal, but I realized that fans might be put off by it. That’s when I thought we needed to approach it more like a fan movie.

Urobuchi: That’s the kind of judgment I leave to the director. I don’t really think about those things (laughs).

Shinbo: A few years ago, I might have said, “This is the only way”, too. But as you get older, you start thinking differently.

Aoki: When I received the file along with the explanation that “the chief director and Kubota-san are feeling unsettled about it”, I was really surprised. But when I listened to it, I thought, “Ah, I see” (laughs).

Iwakami: My impression was a bit different from Urobuchi-san’s. From the script to the storyboard stage, I felt the portrayal was already getting a bit scary. And after the voice recording, it became even scarier.

Kubota: I felt that as the process moved further along, it kept intensifying. The storyboard was already scarier than what I had imagined when I first read the script. Then, the key animator and animation supervisor, Junichiro Taniguchi, really leaned into that feeling when designing the scene. My and Shinbo-san’s role was to make sure it didn’t go too far.

Shinbo: We were making sure we didn’t overdo it.

Kubota: You could tell the staff was really excited about it.

Shinbo: If we hadn’t stepped in, it might’ve never stopped (laughs). With movies, it’s hard to predict how much time you’ll need. Iwakami: You really pulled it all together. Both in terms of content and schedule.

Aoki: The final product had such a delicate balance.

Urobuchi: I think it hit the mark perfectly. Because of how the final portrayal turned out, Devil Homura became such a great character. She didn’t just become a devil—she became Devilman (laughs).

Changing the topic a bit, could you tell us about your interactions with Gekidan Inu Curry?

Iwakami: All the interactions with Inu Curry were mainly handled by Miyamoto-san, Shinbo-san, and the SHAFT team.

Shinbo: We did give them the directive to "make things unique", but I never imagined they’d come up with concepts like that for the café or the crossroads. They definitely made it unique (laughs).

Urobuchi: The characters say "crossroads", so the audience has no choice but to accept it as such. That kind of visual approach is really fascinating.

Iwakami: It’s funny seeing Shinbo-san having to say something sensible for a change.

Shinbo: Right? Normally, I’d be the one pushing for even crazier ideas, but with Inu Curry’s designs, I didn’t need to. Take the crossroads scene—when Homura and Kyoko are riding the bus, I think the less you watch the visuals, the better you’ll understand the story (laughs).

We actually received a comment from Inu Curry about the crossroads, saying, "Since Homura and Kyoko are pure of heart, they can see the crossroads just fine, so there’s no problem".

(Everyone laughs)

Urobuchi: I have no retort.

Iwakami: In other words, "You adults are the impure ones".

Kubota: So, Homura and Kyoko could see it, and the audience probably could too.

Shinbo: It’s just the evil adults who can’t understand (laughs).

As chief director, were you okay with the visuals not fully aligning with the script from the beginning?

Shinbo: I wasn’t fully comfortable with it, but I had a feeling that this wasn’t the kind of project where things should be done normally. Allowing Inu Curry’s designs to pass through felt like a gamble. It would definitely make things harder to understand. The story was already complex, and adding these visuals would make it even more so, especially in a theatrical setting where you don’t have the luxury of rewinding and re-watching. I questioned whether it was okay to create something that’s hard to grasp in a single viewing. But at the same time, I felt, "Well, it’s going to be released as a home video later, so maybe this approach is acceptable". I went back and forth between these feelings. However, I realized that opportunities to express something this unique don’t come often, so I decided to go for it. In a TV show, the dialogue explaining everything would be paired with a simple background, but this time, the visuals themselves carry a lot of information. It might be disorienting, not knowing what to focus on, but I thought it would be fun to have scenes like that.

Urobuchi: In terms of storytelling, I believed the audience would understand they were witnessing an abnormal world. So, even if there’s a disconnect between the characters’ behavior and the audience’s sense of reality, I figured it would still come across. Viewers would realize that if the characters perceive the crossroads in this way, they must be under some sort of illusion. So, no matter how wild the visuals got, I was fine with it.

Aoki-san, as someone who also works as an illustrator, how do you feel about Inu Curry’s designs?

Aoki: My reaction is basically just "Wow" (laughs). It’s such a childlike response, but that’s really how I feel.

Was there anything that particularly stood out to you?

Aoki: Well, since we were inside Homura’s inner world from the very beginning, the entire movie takes place in Inu Curry’s space. Even when we step out of it, we’re thrown into scenes of Homura’s army marching around, and I was constantly like, "What is this!?" I was blown away. And then, there’s that part where the world starts collapsing, with all sorts of incomprehensible things pouring down from above. I loved that scene.

I see.

Aoki: The world Inu Curry creates is so unpredictable that it’s fun to look at no matter where you focus. There are always new surprises, even after multiple viewings.

Shinbo: The children speaking in German really caught me off guard. The attention to detail in the German expressions left a strong impression on me. It’s definitely one of those scenes that sticks in your mind.

Urobuchi: And the fact that Homura's familiars increased in number so dramatically was a surprise too. When I read Inu Curry’s notes, I found out each of them is as strong as a magical girl (laughs). That really shocked me.

What about you, Kubota-san?

Kubota: I’m always amazed by Inu Curry’s work. It’s not just the designs, but their entire process. SHAFT is always trying to create cutting-edge visuals under Shinbo-san’s direction, but for Inu Curry’s sections, they also use analog methods. For example, they hand-colored each frame of Homura as a witch using paint, and sometimes they’d use photographed objects as materials. These are old-fashioned techniques, but in a way, using them now feels fresh. It’s almost like doing something outdated has become avant-garde again. That’s what I was thinking as we worked through the process.

Shinbo: I was worried if they’d be able to finish it all in time…

Kubota: Since the output from Inu Curry’s team is the final piece, you can’t handle it alone when considering efficiency. So there was always some anxiety about whether we could complete everything on time.

Shinbo: If it exceeds the individual’s capacity, you can’t maintain balance.

Kubota: In the end, though, it became an all-hands-on-deck situation.

All-hands-on-deck?

Kubota: Yes, speaking of the coloring process, we printed out the frames on paper and manually colored them, then the digital team would come in and use paintbrushes to fill in the colors. It was a very unusual approach, and it almost felt like an event. It reminded me of the night before a school festival (laughs).

Shinbo: We also had Naito Ken from Studio Tulip involved, along with Yoichi Nangou, known for his unique color work in titles like The Eight Dog Chronicles and JoJo's Bizarre Adventure (OVA). His role was credited as "Alternative Space Art" in this film. It was a lot of fun. I had worked with Nangou-san before and had always wanted to collaborate again, but he’s very insistent on working with analog techniques, so it was hard to find a chance to work together since he avoids digital work. I was really happy to be able to collaborate with him again after so long.

Kubota: The combination of Inu Curry and Nangou-san worked really well. They even experimented with rotoscoping and claymation for the Nightmare sequences. This blending of digital and analog resulted in a technically rich film, in both form and content.

Speaking of digital, I heard that you considered using 3D CG for Kyubey’s animation?

Kubota: Yes, around the end of the TV series, Shinbo-san suggested trying 3D CG for Kyubey to stabilize his expressions. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out as smoothly as we hoped, and we struggled a bit.

Shinbo: It’s strange, but you can’t quite capture Kyubey’s facial nuances without traditional animation. So, we ended up using hand-drawn animation for close-ups and 3D for long shots.

Iwakami: I remember Shinbo-san really liked the scene where Kyubey flies like a sugar glider.

Shinbo: That was really cool. I thought, “Nice work!” (laughs).

Since this film was entirely new, unlike the previous two compilation films, were there any measures taken to improve efficiency during production?

Kubota: This was almost a first-time experience for us, so we didn’t have anything particularly special in mind. But one thing we did was set up a dedicated staff room for the Rebellion staff, concentrating the main team in one place. Since it was an original film, we were especially cautious about managing the story and other information, making sure that everything could be controlled within the studio as much as possible.

Having everyone in one place must have had some advantages.

Kubota: Yes, it minimized the movement of the production team, and it was a huge advantage that key staff, like the key animators and in-between animators, could quickly confirm things. This kind of opportunity is rare outside of a theatrical project.

Iwakami: At the wrap party, I remember SHAFT staff saying unanimously, “We didn’t think we’d finish it”. That left a strong impression on me.

Urobuchi: Well, of course!

Shinbo: You can put endless amounts of effort into a project if you want to. Unless you focus on how to finish it, you’ll never be done. That’s where the director’s judgment comes in. If the director doesn’t aim to finish, a theatrical production won’t reach completion. Just wanting to make something good won’t end it; it will drag on indefinitely. Miyamoto-san, the director, has a great sense of balance in this area, which is why I trust him so much. He can assess how much quality can be achieved within a certain timeframe or when the schedule allows for pushing the quality a bit further.

Iwakami: And the final result wasn’t something that felt rushed either.

Kubota: I can’t take much credit (laughs), but thanks to Miyamoto-san and the entire main staff, everyone worked together really well.

Shinbo: Naito-san, who handled the art, really did a lot this time. This is a bit off-topic, but there’s currently a shortage of art staff in the industry.

Kubota: That’s true. Collecting art staff for both TV series and films is quite difficult right now.

What’s causing the shortage?

Kubota: I think it’s due to the increasing demand for detail in animation backgrounds. Even in TV series, high-density backgrounds are now expected, and the requirements become even higher for theatrical releases. As the demands rise, the workload increases. On top of that, the larger image size for films makes the work even harder. This time, I think Naito-san and his team had a really tough time. When the background art is delayed, it prevents us from seeing the film’s completed form, which in turn delays the process of reviewing the final product. In that sense, we were very fortunate to have the sound team, led by Tsurumaki-san, cooperate with us.

Shinbo: Absolutely.

Kubota: The post-production team was also very patient, waiting until the last possible moment to help us out.

Regarding character portrayal, were there any intentional changes in Rebellion compared to previous works in Madoka☆Magica?

Shinbo: Not at all.

Does that apply to the cast’s performances as well?

Shinbo: Yes. I didn’t want them to change...or rather, the characters were already solidified in their minds, so there wasn’t anything I felt I needed to ask of them.

Urobuchi: If I had to point out one thing, it’d be Sayaka in “sage mode” during her confrontation with Homura.

Shinbo: True, in that scene, we asked for a performance where Sayaka wouldn’t lose out to Homura.

Iwakami: When it comes to adaptations of original works, we sometimes ask the cast to get closer to the character’s image. But with an original work like Madoka☆Magica, the actors’ voices become an integral part of the characters themselves.

Shinbo: Exactly. When that happens, the fans accept any performance, thinking, “This is how the character is now”. Even if it’s different from before, the genuine performance convinces them that it’s authentic.

Aoki-san, did you get the chance to meet the cast?

Iwakami: Perhaps not much during Madoka☆Magica, but many of them are also in Hidamari Sketch. You’ve probably met them through that, right?

Aoki: Yes, I didn’t get to attend many of the recording sessions for Madoka, but I did meet them at Hidamari-related events or after-party venues. I distinctly remember hearing from Yuuki-san early on during the TV series recording that she had just entered university.

It’s surprising that Nagisa and Yuno have the same voice actor…

Aoki: I never expected that (laughs).

Shinbo: We’ve been asking Asumi-san to do a lot of work recently. She’s in Nisekoi, and she’ll be in Mekakucity Actors as well.

It sounds like a very challenging production process, but when did you start feeling confident about the project?

Iwakami: To be honest, from the script stage, I thought it was interesting and had potential. But as the project developed and the amount of information in the animation increased, I became worried. I thought we were making an incredible anime, but I was unsure if many people would accept it. In the end, it was well-received, and the theaters were packed. Looking back, I feel that we aimed really high, and it moved me to realize that there was an audience who appreciated what we created.

Shinbo: Normally, you wouldn’t expect people to want to watch a film twice. Most would see it once, and if they didn’t get it, they’d just move on.

Iwakami: It’s unusual for a film to break those expectations. I’m deeply grateful to the audience.

Did you feel that the project was a challenge as a producer?

Iwakami: I believe it was more of a challenge for SHAFT and the animation staff than for me. This film wasn’t just about spectacle; it pushed boundaries in visuals, storytelling, and character depth. It’s rare to see a movie with such density in all directions.

Urobuchi-san, when did you feel confident about the film?

Urobuchi: When I received the storyboards. The stack of boards was thick like a grudge letter, and I thought, “Are you serious?” (laughs). But I knew if we could pull it off, it would be something extraordinary—and in the end, it really came together, which left me overwhelmed.

What about you, President Kubota?

Kubota: When we finished, I felt that we had given everything we had, and the staff had truly done their best. But like Iwakami-san, I started to wonder, “Did we go too far? Was it okay to go this far? Can this be enjoyed as entertainment?” When it was completed, I couldn’t tell anymore, and I was quite anxious. Not so much confused, but rather concerned that the audience might be put off by it. After the first screenings and hearing the reactions from people seeing it for the first time, I thought, “Maybe it’ll be appreciated, even if I’m not sure it’ll be a big hit”. But even then, I still wasn’t fully confident.

How about you, Director Shinbo?

Shinbo: I felt confident when we completed the transformation scene. We aimed to create a transformation scene unlike any other, and with the combination of the animation and the visuals, I felt like we’d made something new. That’s when I thought, “This will work”.

Iwakami: You could watch that transformation scene over and over.

Shinbo: It became a surreal scene that doesn’t even feel like a traditional transformation.

Kubota: I was nervous about it until the dubbing was finished. The scene was long, and the visuals were unlike anything we’d done before.

Shinbo: The music was great too. Kajiura-san’s work really elevated that scene. It felt like we finally achieved something we had always wanted to do. That alone gave the film its value. I had a sense of accomplishment as a fan. I never expected the film to have such a wide appeal, so I’m really grateful for its success.

How about you, Aoki-san?

Aoki: Like Urobuchi-san, I was already impressed by the storyboards. But at the same time, I kept thinking, “What’s going to happen with this?” So in terms of feeling confident, it was when I received the finished film on a disc and watched it. I thought, “What the heck is this!?” but at the same time, I knew we had made something incredible. However, even then, I was still worried. Since I had already read the script, I could follow along, but I wondered how people who hadn’t read it would take it. With so much going on in the story, I was concerned about how it would be received. Like Iwakami-san, I only felt reassured after seeing the fans' reactions.

Considering how dense the movie is, did you have to be very careful with how you promoted it?

Iwakami: Since Madoka☆Magica's story is so crucial, we wanted to approach the movie’s promotion with the same unpredictability we used for the TV series. While it’s a proper sequel, we also wanted it to be an enjoyable surprise.

Shinbo: I think Iwakami-san made the call on how much to reveal and which scenes to show in the promotional material.

Iwakami: It was actually Kubota-san’s idea to reveal Nagisa early. In many TV anime films, you often see a new enemy character introduced as a guest, and the story revolves around defeating them. We used that pattern to create a bit of a misdirection. Since there aren’t many new characters in that position, I think it worked as an interesting marketing approach.

People quickly started speculating that Nagisa had a connection to the Dessert Witch, which was pretty interesting.

Kubota: There were rumors. It’s amazing how quickly people figure things out.

Madoka☆Magica fans seem to have particularly sharp instincts. The footage revealed on Mezamashi TV also generated a lot of buzz. Was that your decision as well, Iwakami-san?

Iwakami: I discussed it with Kubota-san and Shinbo-san before deciding.

Kubota: It wasn’t like we had that many options (laughs). It was more about choosing from what was already done.

Iwakami: That’s true too (laughs).

I remember the shot of Homura pointing the gun at her head generated an incredible amount of buzz.

Kubota: That was actually released early by coincidence (laughs).

Iwakami: But that shot really stood out. From the moment the storyboards came out, Shinbo-san was saying, “That’s a great scene, right?” It’s an impactful, great shot that also serves as a misdirection.

Aoki: Speaking of that scene, I was curious if it was intentional. Before the movie was released, there were interviews with the voice actors in various media, and someone mentioned something like, “There may be some mixed reactions”. That comment stirred up the audience’s expectations and, in the end, worked out positively.

Urobuchi: Yeah, it felt like we were preparing the audience.

Iwakami: We didn’t correct it because we thought, “Well, that’s fair”, but there wasn’t any calculation behind it (laughs). Shinbo-san, didn’t you say something even more intense?

Shinbo: I said, “Please watch with a strong heart” (laughs).

Iwakami: That’s right (laughs).

Urobuchi: But as creators, that’s just naturally how we feel.

Iwakami: Exactly. While we didn’t want any spoilers about the plot, we also weren’t trying to guide the audience's impressions about what kind of movie it was.

Although the information was tightly controlled before the release, the TV spots that aired right after included some pretty crucial scenes.

Iwakami: Now that I can talk about it, those spots actually aired a bit earlier than planned (laughs). The version with Kalafina’s song was supposed to air a week later, but due to various circumstances, it ended up airing sooner.

Urobuchi: But for people who haven’t seen the movie, those scenes wouldn’t make any sense. If you’ve watched it, you know they’re pivotal moments, but for others, it’s just a series of completely baffling shots.

Kubota: Speaking of releasing information, the idea to attach a teaser to the recap films was Iwakami-san’s idea. I think it worked really well.

Iwakami: I asked Shaft’s team to help out, even though it was a tough ask.

Kubota: The storyboards for the new film had just been completed, and we were about to begin the animation process. At that point, there weren’t any finished art boards. So, with Shinbo-san, Miyamoto-san, and Gekidan Inu Curry’s vision, we created a few early cuts specifically for the teaser. Shinbo-san even added some shots that didn’t appear in the final film. It turned out to be a great teaser that raised expectations.

Iwakami: I was really pleased with that. Kajiura-san even wrote a melody just for the teaser, which later became part of the main score.

Did any of you go to the theater to watch the film?

Aoki: I went once, early in the morning on a weekday.

Shinbo: I went once, because someone invited me.

Kubota: I went three times.

Shinbo: Why so many!?

Kubota: I went back to collect the film strip giveaways (laughs). The first time I went during the giveaway period, I got a background-only frame, and it made me so sad that I went again for a rematch with the staff.

Were you able to achieve your "revenge" with the film strips?

Kubota: Yes, the second time I went, I got a transformation shot of Madoka.

Aoki: Wow!

Kubota: I might have taken that chance away from some fans (laughs).

Urobuchi: I only saw the movie at a private screening. After hearing Kubota-san’s story, I didn’t want to go to the theater and take the giveaways from the fans. I felt a bit guilty about that.

Shinbo: Couldn’t you have just returned it?

Urobuchi: I didn’t want to be seen as the boring guy who gives it back (laughs). Plus, it feels awkward to admit you're part of the production staff while watching.

How was the theater experience for you, President?

Kubota: I went to the first screening on the release day, so I could feel the atmosphere and enjoy the audience’s reactions. For the second and third times, I went to a late-night screening at a local theater, and it was still half-full, so it didn’t feel lonely at all (laughs). Watching something I helped create on the big screen was such a pure joy. It’s rare to have something you’ve worked on shown on a big screen, so that experience alone made me feel incredibly fortunate. I felt that not only for myself, but also for the staff who got to see their work in such a format.

Aoki: The music in theaters is entirely different, too.

Kubota: Definitely! The sound quality and immersion are on another level.

Aoki: Watching it with the surround sound in a theater really pulls you into the world in a way that just doesn’t happen with the discs at home. I hope people who only saw it on Blu-ray get the chance to experience it in theaters.

Iwakami: A revival screening might be a good idea.

How did you feel watching it in theaters, Iwakami-san?

Iwakami: Like I mentioned earlier, I was worried about how the audience would react. As soon as it ended, I found myself looking around nervously (laughs). With a film like this, you can’t expect 100 people out of 100 people to have the same reaction, so the audience's response was a bit mixed. It took me a while to settle down afterward.

Urobuchi-san, did you hear any feedback from your friends?

Urobuchi: I was happy to get positive reactions from my friends. They all seemed to enjoy the unexpected twists, especially since they thought it would just end with Homura ascending, only to be surprised by the continuation. Although I had warned them that there would be mixed reactions, they didn’t seem too shocked by it in the end. In a good way, they accepted it like, “Well, that’s just what Homura would do”. I was relieved that they received it that way.

Shinbo: I’ve said this in other interviews, but in the previous work, it was a mistake for Madoka to make sure only Homura remembered her (laughs). The whole premise of the new film starts because of that decision. Even Madoka’s parents don’t remember her, but she wanted Homura to, which was her mistake.

Aoki: Oh! That makes sense!

Urobuchi: Yeah, Madoka probably still had some lingering attachment to this world. So, in a way, she wasn’t just a passive sacrifice. Homura didn’t completely deny Madoka’s wish either.

That means Homura wasn’t left completely alone—there was still a connection.

Shinbo: Madoka had some lingering attachments too, and that’s reflected in the creators' intentions as well.

Urobuchi: When Shinbo-san mentioned this to me, it really struck me. At the end of the previous work, Madoka became something beyond human, and it could have been a happy ending. But for a middle school girl, carrying the burden of becoming something more than human is way too heavy. She’s still a child, so it’s only natural for her to have doubts and lingering attachments. That thought process led us to continue the story.

Shinbo: I still think it was the right and beautiful ending for only Homura to remember her.

Urobuchi: If Madoka had just happily disappeared at the end, it might have made you wonder, “Did she secretly dislike humans?” (laughs).

Shinbo: But that’s not the case at all. In that sense, the new movie felt like an essential story. It wasn’t just a forced sequel. We were able to balance a meaningful continuation of the story with giving all the characters who had been developed in the TV series and recap movies their moments to shine. I think we were able to meet the fans’ expectations.

Iwakami: It’s amazing that we could incorporate both a proper sequel and showcase the characters’ development.

Aoki: It’s impressive to see that such balance is even possible!

The world that Homura created through her wish manages to balance both aspects. The depiction of a closed-off world that no one notices or can escape from was striking.

Shinbo: In the world of film, not just anime, this type of portrayal has been around for quite some time.

Urobuchi: Yes, it's a recognized genre, where someone becomes trapped in a fictional world. In the realm of bishoujo games, this concept is even more common. Games like Fate/hollow ataraxia, for example. It's a common trope in fan discs for games, so I never felt like I was doing something particularly radical.

Iwakami: Connecting that to something Shinbo-san said earlier, it was interesting to hear, "If Homura had just gone to the Law of Cycles, that would have been the true bad ending".

Shinbo: If Homura had been guided to the Law of Cycles, Kyubey would simply continue doing the same thing. Eventually, the Law of Cycles would be uncovered. Someone has to keep resisting, but if Homura left, there would be no one left to resist. After that, Kyubey could freely experiment with other magical girls, and this time, he might truly capture the Law of Cycles. That would indeed be the bad ending. The story of Rebellion is structured that way.

Iwakami: Homura is acting purely out of love for Madoka, but in the end, she also ends up saving magical girls all over the world, right?

Shinbo: Exactly, so in a way, Homura is affirming what Madoka did. She takes on the mission of ensuring that Kyubey is stopped at all costs.

Urobuchi: Indeed.

Iwakami: A world where Kyubey has observed the Law of Cycles and figured out how to control soul gems, without Homura to stop him, is terrifying (laughs).

Shinbo: Right? That's why Homura had no choice but to act the way she did.

Homura's line, "It's love", also caused a strong reaction, but thinking about it that way, it feels even deeper, doesn't it?.

Urobuchi: Well, you see, the reason I brought up the word "love" was because I was kind of thinking, "When it comes to a power that can even defeat aliens, nothing else fits, right?" (laughs).

Shinbo: However, one thing I want to mention is that, in my opinion, that love feels like it might be "fraternal love" (philia).

Broader than romantic love.

Urobuchi: Romantic love, even when it gets all complicated, stops at Sayaka-chan's level (laughs).

Shinbo: (laughs). That's why I see it as fraternal love, not romantic love (eros). I think that what Homura directs towards Madoka is a broader kind of love.

THE NEXT WORK BY MAGICA QUARTET

Finally, is there anything you'd like to explore in Puella Magi Madoka Magica in the future?

Shinbo: I want to animate Adult Mami (Ara-sā Mami-san), but some of the staff are strongly against it (laughs).

Aoki: Hmm, I want to take better care of Mami-san (laughs). I often find myself daydreaming about Madoka Magica, especially about what happens after Rebellion. It’s hard not to think about it.

Shinbo: Then please go ahead and draw Puella Magi Madoka Magica: The Origin (laughs).

Urobuchi: You can change the original as much as you want. Like how Yoshikazu Yasuhiko reinterpreted Mobile Suit Gundam: The Origin, which is a completely different work (laughs).

Aoki: No way! (laughs).

And how about you, President? Anything you'd like to explore in the future?

Kubota: I'd love to make a sequel (laughs). That's the usual answer, but we really felt something special after making Rebellion. Right after finishing a project, everyone tends to feel, "That's enough for now", but after some time, the main staff starts to feel like, "We want to create more". I sense that everyone feels like continuing.

Shinbo: Especially since everyone’s gotten used to the style. I’m sure the animators in particular want to keep going.

Iwakami-san, what would you like to try next?

Iwakami: I truly believe Rebellion was a miracle. To create something following the huge success of the TV series and to have it reach that level of completion, while also being well-received by fans, is nothing short of a miracle. Of course, we have thoughts like, "Wouldn't it be cool if we could do this next?" If everyone here at Magica Quartet comes up with something we all agree is special, I'd love to work on the next project. But this isn't the type of series where we have to keep making sequels for commercial reasons. We won't make a sequel unless it has a real purpose, so for now, I'm fine with waiting for something truly good to emerge.

Shinbo: I think it would be fun if this became Urobuchi-san's life work, like Tezuka's Phoenix.

Urobuchi: But honestly, I'd like to see a Madoka that has gone beyond my own influence. I think that would expand the scope of the series. For a long time now, I've wanted to see a side-scrolling bullet-hell game with Kajiura-san handling the music and Inu Curry overseeing the art and direction. If someone could make that happen (laughs). You'd shoot down weird witches and familiars at crazy speeds with bizarre weapons, and they’d disappear off-screen at just as crazy a pace (laughs).

Aoki: That sounds like a nightmare to hit anything (laughs).

Urobuchi: It would definitely be something distinctive and absolutely fun.

Iwakami: I seriously want to make that (laughs).

Shinbo: That sounds like fun.

Aside from sequels, what about creating a completely different work with the members of Magica Quartet?

Urobuchi: If we all made something, I feel like it would inevitably turn out to have a Madoka-esque feel, no matter the project. We fit together too well, in a sense.

Shinbo: But I'd like to try something completely different for a change.

Urobuchi: We’d need some specific condition or technique to make sure it steps away from Madoka. Maybe have a story with only male characters, for instance.

Iwakami: Aoki-san, do you find drawing handsome boys fun, or do you prefer drawing cute girls?

Aoki: Well, in the manga I’m currently working on, the majority of readers are male, so when I draw boys, I’m very conscious about not making them into "pretty boys". I avoid making them like boys from shoujo manga and instead aim for characters that feel more approachable, more down-to-earth.

Iwakami: I understand that balance.

Aoki: So if someone told me to draw a "pretty boy", I’d have to switch my mindset completely, and I think it would be a refreshing challenge. I’m curious to see how the art would turn out since it’s not something I’ve done often—only briefly when I was younger.

Iwakami: It sounds like creating a character targeted at female audiences might bring out a new side to your work.

Shinbo: I'd love to try making something aimed at women at least once. It’d be like a learning experience, or something to challenge and conquer—after all, even Gintama is a hit (laughs).

Urobuchi: I know some women who, after watching Koimonogatari, were screaming, "Kaiki!" (laughs).

Shinbo: Really? I love Kaiki too. He’s one of my favorites.

Aoki: He’s so cool.

So, maybe one day Magica Quartet will make something for female audiences... That's a nice note to end on.

Yukihiro Miyamoto

How did you feel about the process from the initial stages to completing the storyboards for the new installment?

The TV anime commercials and the theatrical anime commercials somehow feel different, don’t they? Even though they’re both 15 seconds long, the atmosphere is distinct—it’s like, “Ah, this isn’t TV; it’s a film.” I think it’s not just the difference in quality between TV and theater, but there’s something unique about the way a theatrical production is made, or the ambiance it carries. For Madoka☆Magica, I wanted the commercials to convey that “theater-exclusive” feel just by watching them. I even watched a variety of other theatrical anime for reference and studied them. But in the end, I couldn’t quite figure out what makes something “theatrical” (laughs).

Still, the commercials for the new installment conveyed the atmosphere of a theatrical production quite strongly, don’t you think?

I’m glad to hear that. When I watched the commercial footage, my concerns were about something completely different. Things like, “This footage is unfinished, is it okay to use it?” or “Won’t showing this part now be a spoiler?” (laughs).

In theatrical releases, high-quality visuals are a key focus. What about that aspect?

Director Shinbo said he wanted the visuals to feel like a film, but he also wanted to maintain the essence of Madoka☆Magica. So, while aiming for something cinematic in terms of visual design, we approached the directing and overall atmosphere as an extension of the TV series. I personally think that was the right choice.

It seems your work truly began in earnest after the final version of the script was completed. How was the process of creating the storyboards?

Sasaki-san poured a lot of effort into them, and I felt no anxiety at all because I trusted him completely. Sasaki-san works quite fast, but even so, the sheer volume of work was immense, so he devoted a significant amount of time to it.

The number of cuts exceeded 2,200.

It was a lot, for sure. Considering this as an extension of the TV series, that kind of volume was expected, but for Sasaki-san to handle all that on his own is genuinely amazing. On top of that, the content was dense. Especially the battle scenes between Homura and Mami—Sasaki packed so many ideas into those that when I saw them, I thought, “Whoa!” To be honest, though, my initial reaction was, “This is impossible. If we’re doing this, it won’t be finished until 2020” (laughs).

UTILIZING GEKIDAN INU CURRY'S DESIGNS

What was your impression of the boards and designs created by Gekidan Inu Curry?

They were excellent, of course, and my first reaction was, “This is amazing.” But at the same time, I also thought, “So… who’s going to turn this into actual footage?” (laughs).

For example, the fact that the Nightmare was a live-action puppet seemed like a very unique expression.

It was Doroinu-san from Inu Curry who said, “I want it to be a stuffed doll,” and I responded, “Well, then we’ll have to make it.” So, we requested a company specializing in that kind of thing. However, I was worried about whether we’d have enough time to go as far as animating the live-action footage. The part supervised by Yuya Geshi-san was drawn so well that even if we couldn’t replace it with live-action, the Nightmare could stand on its own as an animated sequence. Ultimately, we managed to complete the live-action work in time, so that was a relief.

The tea party scene where the Nightmare is purified also left a strong impression.

That scene wasn’t in the script; it was an original creation by Inu Curry. The idea was that purifying the Nightmare by satisfying it with food would feel more magical-girl-like. It reflects the concept that magical girl battles aren’t about defeating the enemy but about pacifying them and bringing them to the negotiation table.

Could you share your thoughts on the new characters Nagisa Momoe and Bebe?

Doroinu-san said, “Nagisa is Aoki-sensei’s character, but Bebe is mine!” (laughs). I think the idea was not to alter Nagisa too much but to handle Bebe as a character designed by Inu Curry, especially since Bebe is a witch they created. Doroinu mentioned imagining Bebe as a “silly dog” (laughs). Although Bebe had normal lines in the script, he changed that and wrote all the mysterious language himself. So, Bebe’s lines weren’t ad-libbed—they were all part of the script.

The scene where letters come out of Bebe’s mouth was quite amusing. It felt reminiscent of Maria†Holic, another Shaft anime.

It’s possible that Inu Curry had those past works in mind, but I couldn’t say for sure without asking them directly. The letters that come out of Bebe’s mouth were created by producing all 50 kana characters and digitizing them. That way, they could respond to anything Bebe “said.”

The Witch's Runes also appeared everywhere in the new installment.

We created a font for the Witch's Runes starting with the new installment. Until then, it seems they were painstakingly cut and pasted by hand (laughs). It made things much easier, and I think that’s why we were able to incorporate a lot more of them.

The ideas from Inu Curry seem unique. Was it difficult for you, as someone who had to organize them?

I worked through it by trying to understand their vision in my own way and thinking, "Maybe it’s like this," as I progressed. Whether that was the correct interpretation for Inu Curry, I can’t say, but I would at least present them with my take, saying, "This is how I saw it," and they would adjust things on their end. It was certainly challenging, but on the flip side, without Inu Curry’s input, some scenes might have turned out so ordinary that they’d lack anything interesting visually. That was something I found scary as well.

A MASSIVE AMOUNT OF WORK LEADING TO COMPLETION

You served as series director for the TV series, but for the theatrical version, you were the director. Did you notice any differences in your role?

I feel like the only real difference was the title; the work itself was similar. That said, with the TV series spanning 12 episodes, the sheer volume of material was overwhelming. Compared to that, the theatrical version had about 2,200 cuts, so I wonder if it might’ve been easier in some ways (laughs).

This time, you were credited not only as the director but also for direction.

The film as a whole was divided into five parts, from A to E. Initially, I thought each part would have its own director, and I would only need to oversee their work. However, it turned out that “this person is busy now” and “that person’s schedule is full,” which made me realize we were short on staff (laughs). There was no way I could handle everything alone, so Takashi Kawabata-san shared the workload. For the parts I assigned to him, I could completely trust his work, which was a big help.

The runtime for the new installment is two hours. Was it challenging to fit everything within that timeframe?

Sasaki-san created the storyboards to fit precisely within two hours. This didn’t include the opening and ending sequences, so it ended up slightly over, but I thought, “We’ll manage somehow.” However, Inu Curry then added even more content (laughs). In fact, the tea party purification ritual for the Nightmare was considered as a potential cut.

Were there any scenes that were completely removed?

I don’t think any scenes were entirely cut. Instead, we trimmed or condensed things here and there, and in the end, it was about 1 hour and 58 minutes. There was even a sense of, “Maybe we could still fit in two more minutes.”

SATISFYING VIEWERS WITH THE SHEER AMOUNT OF INFORMATION

When did you feel that the project was finally complete?

When we submitted the final delivery, I felt a sense of both completion and relief.

How did you feel about the reactions from fans who saw the film?

I was nervous. I wondered if we had achieved a level of quality that would satisfy viewers. When I first read the script and storyboards, I found them interesting, so I worked to retain that impression throughout production. But I was still worried about whether that sense of “interesting” was properly conveyed. Of course, we did everything we could, but having seen it so many times, I’d grown accustomed to it and lost some objectivity, which made me anxious.

But once it was released, it was a huge hit.

It was amazing that everyone understood and accepted the content. I think that’s incredible.

Some people watched it multiple times to analyze and interpret it.

That’s something I’m very grateful for. At the same time, it’s a bit scary, as if they’ll see through every little flaw (laughs). As one of the creators, I watched it repeatedly myself, but even then, I think it was about 500 times—not the entire film, but individual cuts played on repeat. Some fans mentioned watching it ten times, and I’ve met people who noticed details I wasn’t even aware of. Sometimes, certain things just happened to look meaningful when they weren’t intended to be. I felt a bit bad for ruining the illusion (laughs).

I think that's why this work is so worth considering and interpreting.

Thanks to Inu Curry and everyone else, a lot of elements were packed in. Even without me doing much, the sheer amount of information just kept increasing, which made things a lot easier for me (laughs). When the film was completed, I found myself focusing on the flaws and shortcomings, wondering, “Is this really okay at this level?” But Sakai (Motoi)-san, who handled the visual effects, reassured me, saying, “It’ll be fine. The sheer volume of information will overwhelm viewers to the point they won’t even notice any flaws.” That made me realize, "Ah, so overwhelming them with information is a valid approach" (laughs). Additionally, unlike TV recordings, you can’t pause or rewind a movie in the theater, which, in a way, works to its advantage. As the visuals keep progressing rapidly, new information is presented one after another, drawing the audience into the film while overwhelming them with the sheer density of it.

Fans are curious about the ending. The moon is split in half—what’s the meaning behind that?

That idea came from Inu Curry. It’s not a crescent moon but a depiction of it being physically cut in half. Of course, it doesn’t mean the actual moon is like that—it’s more of a symbolic image.

Kyubey’s clouded eyes also left an impression. What’s the story there?

We’ve deliberately left several mysteries like that. Most of them were probably the work of Inu Curry. As for Kyubey’s state in the final scene, that was already depicted that way in the storyboards. However, I believe the scenes after the ending theme were primarily expanded and added by Inu Curry. Once again, thanks to the additions and embellishments made by Inu Curry and everyone else, the film has received such positive acclaim. For my part, I feel a bit like “Heh, it all worked out nicely.” Even though I just rode the wave of everyone’s efforts, we were able to create something that fans are satisfied with, and I consider myself very lucky for that.

Shinsaku Sasaki

INVOLVEMENT WITH MADOKA☆MAGICA SINCE THE TV SERIES

Sasaki-san, you’ve been involved with Madoka☆Magica since the TV series.

I was invited to participate by Iwaki (Tadao)-san, who was the animation producer of the TV series. Until then, I had never worked with Studio Shaft, but I was, of course, aware of them as a studio that created unique visuals. However, I felt that their approach to animation and their philosophy were somewhat different from my own, and I never imagined I’d have the opportunity to work with them. By chance, I was invited, and when I read the plot and script, I found them incredibly interesting. I remember thinking, "Am I really allowed to participate in such a project?"

What were your impressions when you read Urobuchi-san's script?

Honestly, and I say this with all due respect, I initially misunderstood and thought, “A brilliant new writer has emerged!” At the time, I wasn’t aware of Urobuchi-san’s established reputation in the gaming industry or that he had already written several anime scripts. His script differed slightly from the screenwriting conventions I was familiar with, but I found it personally easy to translate into storyboards. The scripts clearly conveyed the necessary visuals, and I was deeply impressed by the strong dramatic world that existed within Urobuchi-san’s mind.

What were your impressions and experiences while storyboarding the TV series?

This relates more to Studio Shaft’s style than to Madoka☆Magica, but I had the impression that Shaft had a production style where they invested heavily in certain parts of the animation while simplifying others to streamline production. However, with Madoka☆Magica, I found it difficult to gauge the volume of the action scenes. For the first storyboard I worked on (Episode 4), I drew the action scenes rather simply, attaching a note saying, "Feel free to make adjustments if it doesn’t match the intended image." When the final animation was completed, I was surprised by the sheer number of cuts it had. The production team seemed to be very engaged, and the staff appeared to tackle each episode with enthusiasm. It was a wonder how the team managed to maintain this level of intensity throughout the production, but I think Madoka☆Magica came together exceptionally well.

REGARDING GEN UROBUCHI'S SCRIPT AND GEKIDAN INU CURRY'S DESIGNS

After working on the two-part movie, you also handled storyboards for the new chapter (Rebellion).

When I first read the script for Rebellion, I found it incredibly challenging. I thought it must have been immensely difficult for Urobuchi-san to come up with a continuation to a story that had already concluded so perfectly. Reading the script, I felt a sense of responsibility to take on the confusion and challenges of creating something entirely new. It seemed like a daunting task. Another thing I noticed was that the writing style had changed. In the TV series, the descriptive detail in the scripts increased as the story approached its climax, but in Rebellion, the descriptions became much simpler. This meant I had to consider the scenes and situations more thoroughly myself, but that wasn’t particularly unusual for a Shaft production. I imagine that, having already experienced Shaft’s approach to visuals in the TV series, Urobuchi-san might have thought, "I’ll leave this up to Shaft; they’ll take care of it."

What considerations went into translating the script into storyboards?

Initially, I wondered if I should create something uniquely suited for a theatrical release. However, as I worked on it, I realized that approach didn’t suit Madoka☆Magica and made the storyboarding process difficult. I quickly gave up on that idea and shifted to storyboarding as an extension of the TV series, which made the work much smoother.

Did you collaborate with Gekidan Inu Curry while storyboarding?

By the time I began storyboarding, Gekidan Inu Curry had already created a substantial amount of settings. I thought, "With this much material, I won’t have any issues while storyboarding." However, as I progressed, I found myself wanting even more. While their script was excellent, there were moments when my storyboard work and their design work overlapped, and we couldn’t fully coordinate due to time constraints. As a result, there were elements I couldn’t utilize in my storyboards, but they later enhanced those with their own work.

What initial settings from Gekidan Inu Curry were there?

I believe the café scene with Homura and Kyoko was present from the start. The flying ship and the children of the fake city also appeared early on. Additionally, the concept for the bus scene was available fairly early. Then came the settings for the Nightmares, in that order.

Were there any settings you created while progressing with the storyboards?

For example, the room where Mami was, Hitomi’s bedroom, and the ghost town where Homura and Mami fought were first drawn by me. Later, Gekidan Inu Curry turned them into concept art. For everyday scenes or locations not central to the story’s core, I worked on them with the idea that it would likely be acceptable to proceed with my designs. One notable example wasn’t exactly a setting but rather a recurring idea I contributed: the park overlooking the city, which appears multiple times as a key scene. Inspired by the initial key visual of the five characters standing together, I wanted to include a scene where they all watch the sunrise after the Nightmare battle.

BRINGING AN ENORMOUS NUMBER OF STORYBOARD CUTS TO LIFE

It was surprising to many anime fans that Rebellion had over 2,200 cuts.

However, in Shaft’s anime productions, it’s not unusual for a single TV episode to have around 400–500 cuts. By that standard, it was inevitable that the total number of cuts would reach such a high count. It seems that your approach to the storyboards followed naturally as an extension of the TV series.

Let’s talk about specific scenes. How was the battle with the Nightmare at the beginning?